Introduction

As part of the Active Transportation Plan, MVPC staff solicited input from people living near shared used paths across the region. The abutters survey was intended to gather information about the experience (good or bad) of living near a path and how planning can incorporate lessons learned from abutters’ experiences. Learning about the experience of people who either moved to the community before or after the completion of a shared use path will inform how MVPC and the region’s communities shape their public engagement practices for future projects.

Methodology

MVPC Transportation Staff identified households within 300 feet of a shared use path in the region using MVPC’s MiMap GIS service for each community. Staff created an online survey using ArcGIS’s Survey123 application and created postcards with a QR code and link to the survey (see postcard below).

Response Rate

Staff sent a total of 2050 postcards to abutters throughout the region and received 62 responses for a response rate of 3%. The table below breaks down the response rate by community.

| Community | Postcards Sent | Responses | Response Rate |

| Amesbury | 104 | 4 | 4% |

| Lawrence | 475 | 4 | 1% |

| Methuen | 330 | 2 | 1% |

| Groveland | 184 | 8 | 4% |

| Newburyport | 620 | 32 | 5% |

| Salisbury | 214 | 6 | 3% |

| Haverhill | 124 | 6 | 5% |

| Total | 2051 | 62 | 3% |

Influence on Renting or Buying

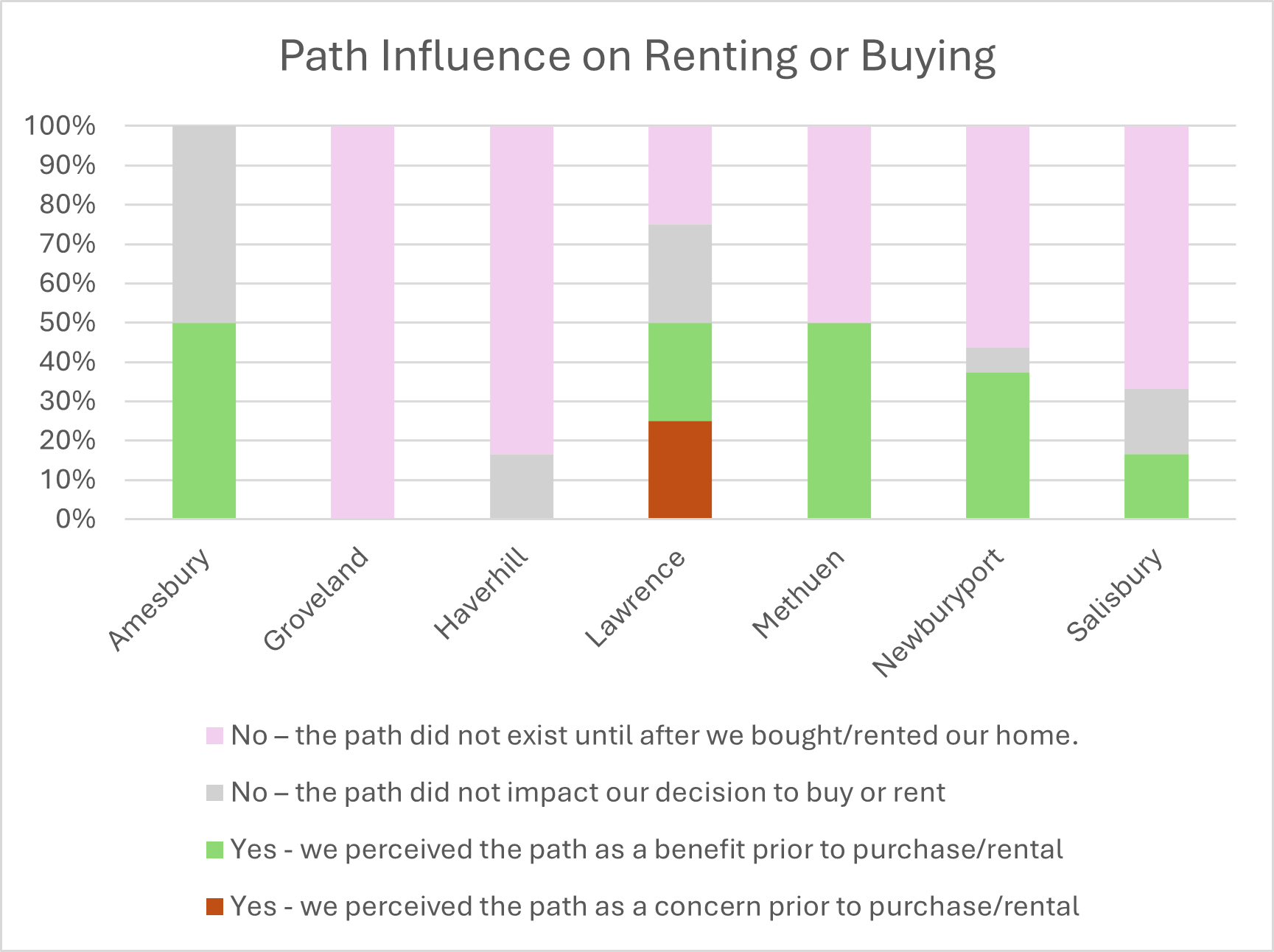

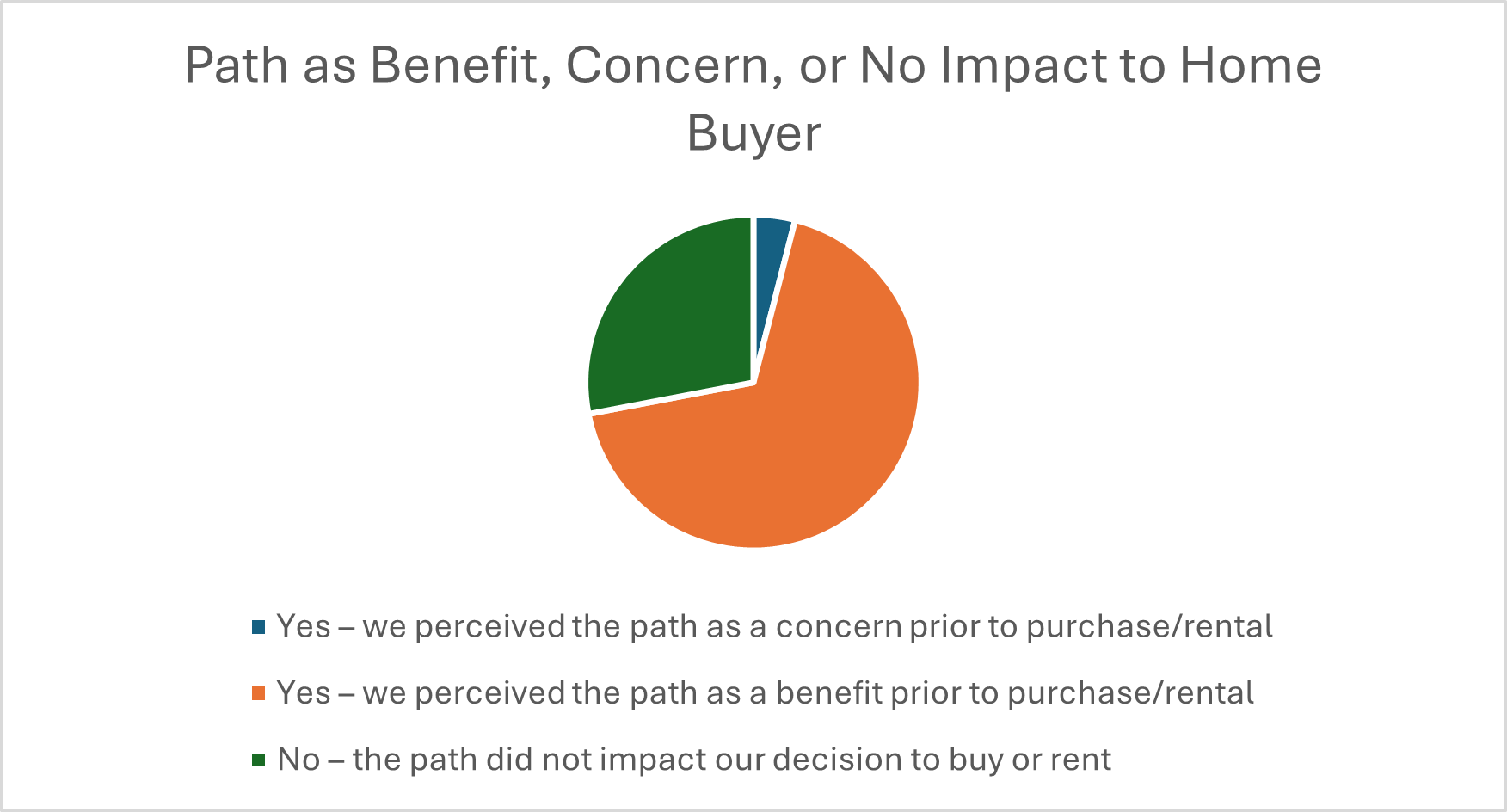

Overall, 57% of respondents were already living in their home when construction of the shared use path was completed. Of the respondents who chose to rent or buy a home near a completed shared use path, 65% perceived it as a benefit, 27% reported that the shared use path did not impact their decision, and 4% reported that the shared use path was a concern.

Path Use Frequency

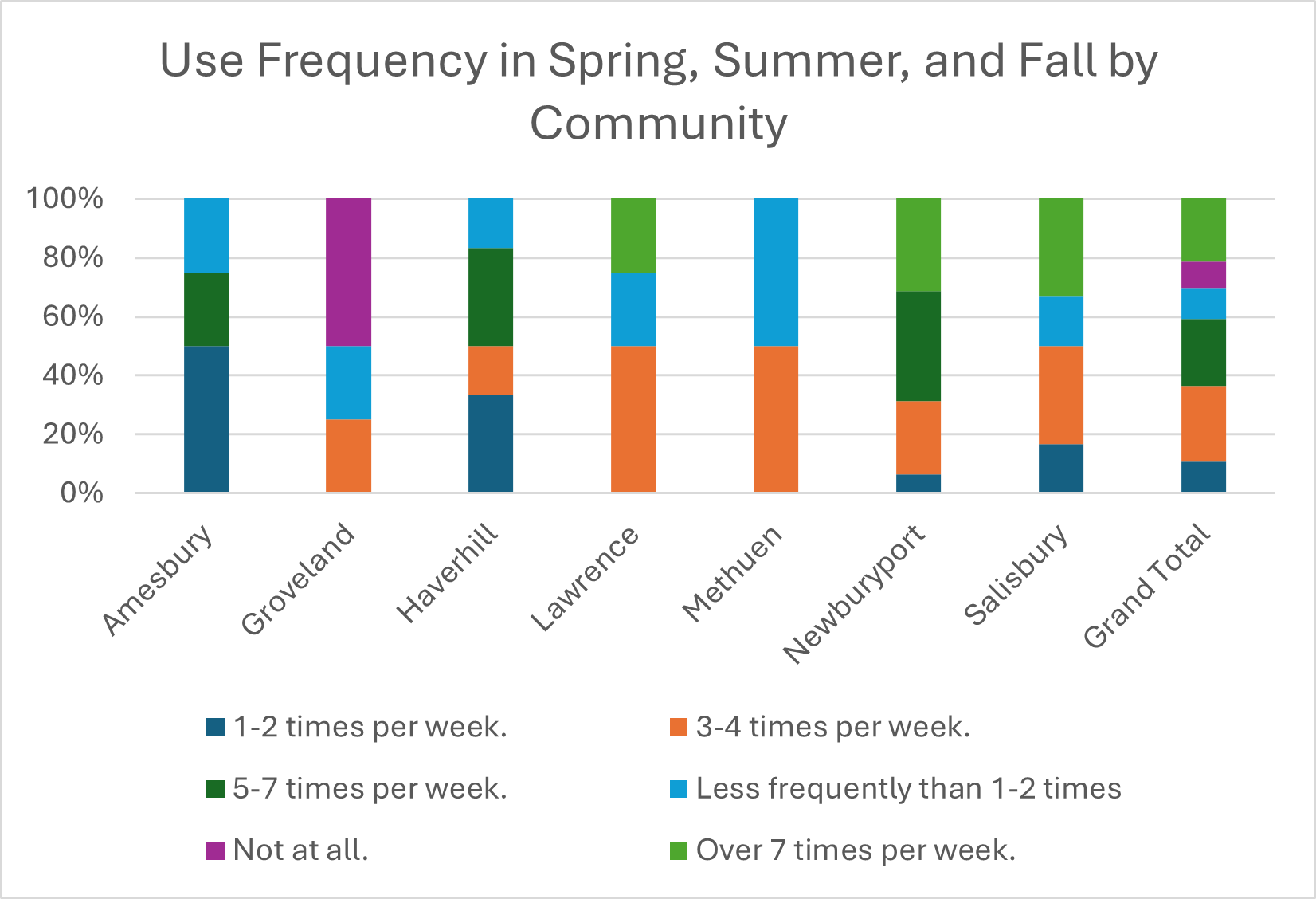

70% of respondents use the path they abut at least 3-4 times per week. Groveland had the highest percentage (50%) of abutters who answered that they do not use the path at all. Salisbury (33%), Newburyport (31%), and Lawrence (25%) had the highest percentage of respondents who use the path over 7 times per week. 68% of all respondents reported that they use the path with other people. 43% of respondents reported that they use the path for socially-oriented recreation.

Improvements to the Paths

Seven themes arose from the responses to the question “What improvements could be made to improve the experience of living near or using the shared use path?” These themes were:

- lighting (12)

- maintenance (10)

- trash (9)

- connections (6)

- people (6)

- speed of bikes (5)

- dog waste (4)

Lighting

Respondents from most communities reported a need for better lighting along the paths. The need for more lighting was also a frequent comment that staff heard during intercept surveys. Also consistent with comments received during intercept surveys were, two responses noting that sections of the Newburyport path are dark and feel unsafe especially for women. The sections of the path that feel unsafe when dark go through areas with less activity and fewer access points. Another respondent reported that there are sections of the Marsh Trail in Salisbury that need lights. There are long stretches of the East Marsh Trail that are heavily wooded and are only activated by other path users. There was a respondent from Lawrence who reported that “lighting is key to enjoying our family walks after dinner.” This respondent reported that they use the trail 3-4 times per week. There was one respondent from Groveland who proposed not adding lighting to the path; the same respondent also reported that they use the path less than 1-2 times per week.

Maintenance

Respondents noted that improvements to snow plowing, mowing, clearing vegetation overgrowth, and fixing fences could enhance the quality of the path experience. Respondents stated that the path and the sidewalks that lead to the path should be regularly maintained to improve the user and neighborhood experience. One respondent wrote “Regular maintenance–sweeping, mowing, trimming. Path is just a terrific betterment for the community”. One respondent noted that they do not want to hear noisy maintenance before 9am.

Trash

The need for frequent trash receptacles at the entrances and along paths was a theme that is consistent with what staff heard during the intercept surveys. One comment noted that trash should be picked up more frequently – it is unclear whether the respondent meant picking up litter along the path or emptying trash receptacles. One comment from a Methuen respondent was clearer, stating that litter needed to be cleaned up along the paths.

Dog Waste

Respondents noted that dog waste can be an issue. Certain path users leave dog waste either in bags or simply on the ground along the path.

Connections

Two comments called for wider paths along with better connectivity of the path network. A few people in Newburyport mentioned wider paths during the intercept surveys. There were comments that stated a need for better sidewalk connections to the paths and better connections in places with high traffic volumes.

People

In the gateway cities of Haverhill, Lawrence, and Methuen, respondents reported a need to address unhoused people living along the paths in those communities. The housing crisis and lack of affordable shelter for community members is beyond the scope of the Active Transportation Plan but warrants discussion. Determining the cause of why people choose to live along paths and potential courses of action to address their needs may be a recommendation of the plan, but the complexity of the topic extends beyond the scope of this plan.

Two Groveland respondents mentioned concerns about a lack of privacy after the path was completed. One person noted that they intentionally bought a home to be away from human activity, and seemingly, the path has disrupted their desired lifestyle. Both respondents suggested that the addition of dense shrubs or evergreens would improve the experience of living next to the path. On the other hand, a Groveland respondent stated “we can see the path from our deck/windows, and it has not been a problem at all. It is pleasant to see people walking and children enjoying themselves on the path. The fence was a nice addition. I have no complaints at all, well done!”

There were also two respondents who reported concerns about people trespassing through private property to access the path.

Speed of Bikes

Respondents noted that signage reminding bicyclists to alert pedestrians as they pass are needed. Respondents suggested that lane lines and signage would help establish etiquette along the path. One respondent suggested that Ebikes and other motor vehicles should not be allowed on the paths.

Takeaways

Respondents provided several areas of focus for public engagement and design as the region looks to advance the active transportation network. For example, conceptual plans may depict how designs preserve privacy for residents in more remote neighborhoods. The design of the path should strategically enhance activity nodes while also respecting the privacy of neighbors. The placement of authorized access points to a path can be crucial in encouraging path users to access the path without trespassing on private property. Design features such as wayfinding signs, trailheads, and maps can encourage people to get to the path along accessible routes and find authorized parking.

The design of a path should allow for a safe and comfortable experience for all path users. Lighting is a design element that would allow people to feel safe at all times of the day and night. It is helpful to know that most abutters who use the path want to see better lighting, as they would also be potentially impacted by increased light through their windows. Implementing context sensitive lighting that illuminates the path and does not spill into the windows of abutters may improve the feeling of safety along the path network. The image below shows an example of lighting that is pedestrian oriented and may not disturb surrounding environments.

Path Lighting (Source: https://rclite.com/blog/how-to-light-a-path-with-bollard-lights/)

As the name suggests, shared use paths are used by people using different modes of transportation that move at different speeds. Paths should be designed to minimize conflicts between modes and encourage faster modes to use caution and yield to slower modes when passing. More specifically, lane markings may encourage people walking to stay to the right and people biking to use the left lane to pass. Signage encouraging people biking to alert themselves as they pass people walking may promote shared etiquette among path users. Wider paths may be warranted in high traffic areas to allow enough space for people moving at different speeds to pass with minimal conflict.

As paths go through the design process, it may be worthwhile for municipalities to develop a maintenance plan for the path. Setting expectations for who is responsible for maintenance and how frequently maintenance will take place may result in a more pleasing experience for path users and neighbors. Maintenance, including emptying trash receptacles and refilling dog waste bag stations, requires either employees or volunteers. If a path is to have more trash receptacles and other elements that need upkeep, there should be designated people, organizations, or municipal departments who are responsible for the upkeep. Funding for maintenance employees or agreements with volunteers should be established as paths are constructed.

Conclusion

Most people who live near paths use them frequently – at least 3-4 times per week. People use them for a variety of reasons, especially for recreational and exercise activities. Often those activities are done with other people, offering a social benefit to living near a path. There are ways to improve paths so that they respect the neighborhood character, but there is an inherent social element to shared use paths. If a community is planning to implement a shared use path, abutters engaged in the planning process may want to know how the path can be designed to limit concerns and enhance the benefits of having people passing by their property.